[et_pb_text admin_label="Chris Fitzgerald byline; remember to tag post as various-contributors" saved_tabs="all" background_layout="light" text_orientation="left" header_font="Arimo||||" text_font="||on||" use_border_color="off" border_color="#ffffff" border_style="solid"]

The classification that opens the entire east side of Case Inlet from Rocky Bay to Longbranch, including Vaughn Bay and Dutcher’s Cove, to commercial shellfish farming, is scheduled to be complete by spring of this year, according to Bob Woolrich, manager of growing Areas for the Office of Shellfish and Water Protection of the state Department of Health (DOH). On the west side of the peninsula on a “half-mile or so” stretch just south of Minter Bay, Woolrich indicated Minterbrook Oyster has asked for additional approved classification for beaches adjoining those they already farm; Woolrich says this is the only “west side” classification request at this time.

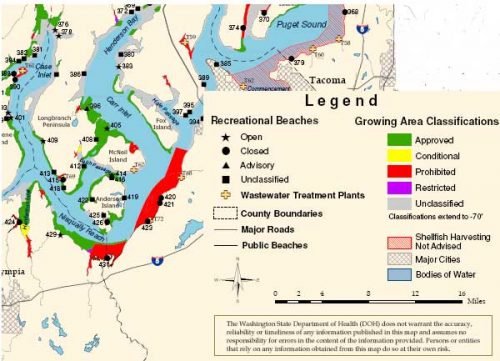

The map shows the upcoming classifications of the east shoreline of the entire Key Peninsula to “approved” commercial shellfish farming is outdated. Find Rocky Bay on the map, and follow the gray-colored shoreline all the way down to Longbranch, including Herron Island. All the gray areas, by spring, will be green. This is the color signifying tidelands to minus-70 feet, both public and private, are “approved” for commercial shellfish cultivation and harvest. Map courtesy Washington State Department of Health

The map shows the upcoming classifications of the east shoreline of the entire Key Peninsula to “approved” commercial shellfish farming is outdated. Find Rocky Bay on the map, and follow the gray-colored shoreline all the way down to Longbranch, including Herron Island. All the gray areas, by spring, will be green. This is the color signifying tidelands to minus-70 feet, both public and private, are “approved” for commercial shellfish cultivation and harvest. Map courtesy Washington State Department of Health

A recently released Geoduck Clam Research and Management report by Pacific Shellfish Institute identifies the South Puget Sound region to be of special interest to geoduck farmers because of its water clarity and abundance of other shellfish. Other healthy, growing species indicate abundant phytoplankton and nutrients, necessary resources for successful aquaculture geoduck farming. The largest commercial shellfish grower/processor in the state, Taylor Shellfish, is located within that region, in Shelton.

The report notes the “proximity to current culture operations… reduces travel time and cost by eliminating additional infrastructure in other areas.” South Puget Sound Department of Natural Resources-owned tidelands are cited as holding “promising characteristics.” In addition, the document says, “South Puget Sound also has substantial concentrations of wild geoduck — (again) a promising characteristic for farm siting.” The report does not mention the industry practice of removing all wild geoduck, and other living species, from the site of a new farm prior to “planting.”

Cathy Barker at DOH said that, about five years ago, Taylor Shellfish and Seattle Shellfish requested the Case Inlet tidelands, which were then “unclassified,” to be classified “approved” for shellfish production. Additionally, Woolrich said about two years ago, he was also asked by the Puyallup Tribes to open Vaughn Bay specifically for commercial harvest.

The process of taking unclassified tidelands to one of several classifications takes the DOH from two to five years. It begins with 30 water samples taken over several years in all weather, seasons, and tide levels. A shoreline survey is done to “look at the shoreline very carefully for any pollution sources.” He cited several examples of pollution, such as failed septic tanks, extraordinary numbers of wildlife, livestock, and boating activities. After requirements for a desired classification have been met and the area is classified, Woolrich said the DOH takes water samples six times per year, “tries to” look at each site every three years, and is mandated to “scrutinize the site” every 12 years.

Woolrich stressed the DOH has a narrow focus and is only concerned with and controls the harvest of shellfish, not permitting, planting, etc. For those issues, he said, people need to look to the Department of Ecology, DNR, or Fish and Wildlife. Woolrich admited that “commercial growers can get ahead of us,” and that his staff primarily looks for three conditions: chemical contamination, biotoxins, and oily spills.

In response to a question about South Puget Sound areas (Totten Inlet and Zangle Cove) that environmental groups claim to have been polluted primarily by an overabundance of monoculture farming, Woolrich replied, “Pollution of water is another agency’s problem unless it affects human health. Environmental impacts of affecting fish and shellfish are not issues DOH looks at. People expect geoducks and oysters to be alive when purchased; if the shellfish die, people will not buy them, so it’s not a DOH problem.”

The classification of the entire east shoreline of Case Inlet coincides with at least two geoduck application permits that have been approved, appealed, and reconsidered (SD55-05 and SD53-55) in Vaughn Bay, scheduled for “approved” classification by spring. Without the classification to “approved” status, geoduck farmers can plant and cultivate the clams, but not harvest them, as harvesting is controlled by the DOH. Regardless of whether growers plan to plant on either private or DNR tidelands, they are required to comply with DOH classification standards for harvest.

Geoducks, anyone?

Bob Downen, a Longbranch resident for many years, wonders where the geoducks went. He says people used to sell them at roadside stands all down the peninsula. “None of the supermarkets carry it; the clerks don’t even know what geoducks are,” he said. “Johnny’s Seafood Market in Tacoma referred me to the Asian markets.”

He remembers when the clam sold for 25 cents a pound, and says he “can’t get much enthusiasm (for all the farming) when geoduck isn’t even available for the U.S. public to purchase.” Downen has no objection to farming, as long as “it’s done in a logical, good cyclical way with regulations that don’t destroy the sea as a resource.”[/box]

UNDERWRITTEN BY THE FUND FOR NONPROFIT NEWS (NEWSMATCH) AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, THE ANGEL GUILD, ADVERTISERS, DONORS AND PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT INDEPENDENT, NONPROFIT LOCAL NEWS