Editor’s note: This is the first of a three-part series on logging on the Key Peninsula. The first article provides an overview of permitting requirements and an example of what happens when the rules are ignored. The second article covers the practice of clear-cutting, and the final article will discuss alternative forestry practices.

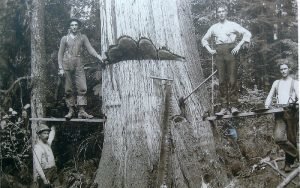

Cutting down a cedar tree on the Key Peninsula, circa 1920. Settlers William and his son Harry Creviston on right. Photo courtesy KP Historical Society

Cutting down a cedar tree on the Key Peninsula, circa 1920. Settlers William and his son Harry Creviston on right. Photo courtesy KP Historical Society

When white settlers first came to the Key Peninsula in the mid-1800s, the density of the forest and massive size of the trees was dazzling, according to R.T. Arledge in his book, “Early Days of the Key Peninsula.” He wrote that the cedars were so big, they sometimes served as dwellings for the newcomers. Indians had seasonal villages, but there is no evidence of permanent settlements on the peninsula.

Logging operations first started in the 1860s. Initially limited to the shoreline, logging depended on high tides to transport the fir and cedar, and loggers were fed and housed on floating camps.

In the 1880s, families came to the Key Peninsula with plans to farm. After arriving and cutting timber for their homes, many realized that the trees had significant value. Skid roads were built to transport logs using horses and oxen, and some of those roads are still in use.

The economic crash of 1891-93 led to a slump in the market value of timber, and many loggers turned to farming or moved on to other operations in the Northwest, though some remained to work for themselves

Logging on state and private land was first regulated in 1974, when the Forest Practices Act was adopted. That law was designed to protect Washington’s public resources and maintain a viable forest products industry, according to the Department of Natural Resources.

A state permit to log is required if the landowner has no plan to convert the property to other use. Stumps are left in place and it is assumed the forest will grow back.

“Ninety-nine percent of logging permits on the Key Peninsula are from the state, and requirements are not as restrictive as they are with the county,” said Adonais Clark of Pierce County Planning and Land Services (PALS). “They are exempt from the 50-foot buffer along KP Highway and State Route-302, public notice is not required, and logging in forested wetlands is allowed.”

There is a six-year moratorium on development of land when it is logged with a state permit.

A county permit must be obtained if land is to be logged and cleared for development, if stumps are to be removed or if trees removed are more than 150 feet away from an existing building.

A county permit must be obtained if land is to be logged and cleared for development, if stumps are to be removed or if trees removed are more than 150 feet away from an existing building.

A county permit requires a 50-foot buffer along KP Highway and SR-302, as well as public notice, except for construction of a single-family residence or clearing for pasture. Because it is assumed that the forest will be gone forever, county rules focus on protecting wetlands and streams due to permanent ongoing impacts associated with development, such as noise, light and water pollution. Logging in wetlands is not allowed. When illegal activity occurs, an official response is activated.

The following case illustrates both the power and the limits of that response.

In May 2014, neighbors became concerned about activity on a parcel of land in the Longbranch area. It appeared that people had moved onto the property, were living in RVs or trailers, and had begun to cut down trees.

The first action was a call to Piece County Responds. Established in 2002, this code-enforcement agency serves as a clearinghouse for complaints. The Solid Waste Division of Public Works and Utilities oversees the program and coordinates with PALS, the Sheriff’s Department, the Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department and the Pierce County Prosecutor’s Office.

Steve Metcalf, representative for the health department, reviewed the action that followed the complaint.

The land was purchased through an owner-financed agreement and when the complaint was lodged, the health department, Solid Waste Division and PALS were alerted. In June 2014, the county confirmed that people were living on the site illegally, that they had dumped solid waste, and that raw sewage was flowing onto the property from their RV.

The health department issued a notice of violation to the owner. In December 2014, when the owner did not respond, notification was sent that legal action would be taken, with cleanup at the owner’s expense. When officials inspected the property in February 2015, the property had been largely cleaned and the RV was gone. Ownership reverted to the original owner in March and the health department deemed the cleanup complete. No further legal action was taken and the case was closed in November 2015.

But the story does not end there. In addition to the concerns about solid waste and raw sewage, logging and wetlands violations had occurred. In August 2014, PALS was called to investigate illegal clearing in the wetland on the property. Mary Van Haren, a PALS enforcement biologist, reviewed the steps her department takes. “Enforcement is reactive, not proactive. We respond to complaints,” she said.

Once a complaint is received, the owner is informed of the violation and what must be done to come into compliance. The owner has 60 days to take action. If nothing is done, enforcement follows.

First, a record of noncompliance is placed on the title for the property. If there is such a notice, banks won’t lend money to finance buying it, so unless the buyer pays cash or the owner finances the sale, the property cannot be sold. There are also civil penalties. Fines begin to accrue, starting with a fine of $1,000, then an additional $4,000 and finally an additional $10,000 if no action is taken. If unpaid, the fines are sent to collections.

In this case, the owner never responded to the notices, both posted and mailed between August 2014 and early March 2015. The original owner resumed control of the property in mid-March and met with PALS staff. Although much work was done to clean the parcel, PALS required additional work to mitigate the clearing done in the wetlands. That work was never completed, and a notice of noncompliance was placed on the title.

Over the course of eight months, after an owner-financed sale, the buyers violated multiple regulations and refused to repair the damage they had done. When the owner finally regained control of the land, he was held responsible for the damages and a record of noncompliance mars the title. As Van Haren noted, if a violator chooses to ignore the authorities, the ultimate consequences and final repair may come only when the owner tries to sell the land.

Legally permitted logging, primarily clear-cutting, is the most visible logging practice on the Key Peninsula and raises many issues. Some worry about the view, others about the environmental impact. Loggers describe timber as a crop, ripe and ready to harvest. The next article will review those issues and the economics of logging.

To report a suspected violation, call Pierce County Responds at 253-798-4636, or report online at Code Enforcement

UNDERWRITTEN BY THE FUND FOR NONPROFIT NEWS (NEWSMATCH) AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, THE ANGEL GUILD, ADVERTISERS, DONORS AND PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT INDEPENDENT, NONPROFIT LOCAL NEWS