Map: Washington State Department of Natural Resources

Map: Washington State Department of Natural Resources

The extensive shoreline and waters surrounding the Key Peninsula and McNeil Island have long been recognized as important habitat for flora and fauna in south Puget Sound. In early December, staff from the Washington Department of Natural Resources and the Nisqually Reach Nature Center addressed a gathering at the Longbranch Improvement Club about plans to improve protection of that habitat.

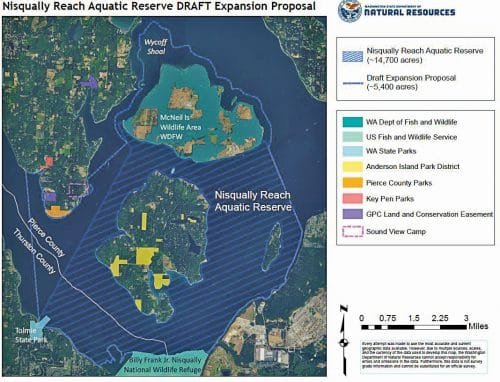

DNR proposes expanding the boundaries of the Nisqually Reach Aquatic Reserve to encompass state-owned aquatic lands surrounding the north side of McNeil Island and the south end of the Key Peninsula that includes Sound View Camp, Devils Head and Taylor Bay. The expansion would provide resources to monitor, protect and restore habitat.

The Nisqually Reach Aquatic Reserve was established in 2011 and includes the lands on the south end of McNeil, a site identified in a 2006 DNR study as a top priority for preservation. The state recently discovered that aquatic lands on the island’s north side are state rather than federally owned, prompting a plan to expand the reserve.

Dan Hull, executive director of the Nisqually Reach Nature Preserve, played a lead role in sponsoring the expansion proposal. He said that as the committee worked on the proposal, they decided to include the waters around the south end of the Key Peninsula. There are several unique habitat areas, including a sandspit, saltmarsh and a bull kelp bed. “And there are valuable upland partners,” Hull said, citing conservancy lands and Sound View Camp as examples.

“It is much easier to protect than to restore habitat,” Hull said. This expansion will include Wycoff Shoal north of Pitt Passage and its eelgrass beds, intertidal forage fish spawning habitat, a pre-spawning herring holding area, the largest seal pupping area in the south Sound and a unique deep-water rockfish habitat. Important birding areas for grebes, loons and ducks are also included.

Questions from the audience included concerns about how a reserve might affect the beach property owners and fishing and boating in the area. “It is much easier to protect than to restore habitat.”

Roberta Davenport, aquatic reserves program manager, said that owners of shoreline adjacent to a reserve should not be affected. All licensed activities such as fishing, crabbing and harvesting of native geoducks will continue to be managed by the Department of Fish and Wildlife with no resulting change in the rules. She explained that throwing an anchor in eelgrass, provided it did not lead to dragging and disrupting the bed, would not be prohibited. New leasing agreements would require that the management goals of the reserve would have to be met, so that, for instance, shellfish farming on the McNeil shoreline would not be allowed.

A benefit of establishing a reserve is the existence of state staff that help focus and manage the program. They include the manager, an educator, six field staff, a marine ecologist and someone to manage GIS and data. Partnering with organizations and citizen-scientists to help monitor the shoreline, participate in bird counts and run educational programs are all part of the reserve program.

The technical advisory committee completed its recommendations in May. Its recommendations were then reviewed by tribes and other stakeholders including the shellfish industry and land trusts before public meetings in December. A State Environment Policy Act review will be the final step before the expansion is official.

The aquatic reserve program, established in the early 2000s, is designed to protect important native ecosystems on state-owned aquatic lands. To be considered, a potential site must address environmental, scientific or educational needs. The process to establish or to expand a reserve is a lengthy one, involving scientific scrutiny and public input.

“The site must have something special and the ecological resources should be high quality,” Davenport said, adding that if the area has been significantly degraded it may be too much of a challenge to restore. There are now eight reserves in the state. The most recent, Lake Kapowsin, is the only freshwater reserve. The rest are in Puget Sound and include Cherry Point, Cypress Island, Fidalgo Bay, Smith and Minor Islands, Protection Island, Maury Island and Nisqually Reach.

Anyone with questions or comments can contact Roberta Davenport at 360-902-1073 or email roberta.davenport @dnr.wa.gov.

UNDERWRITTEN BY THE FUND FOR NONPROFIT NEWS (NEWSMATCH) AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, THE ANGEL GUILD, ADVERTISERS, DONORS AND PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT INDEPENDENT, NONPROFIT LOCAL NEWS