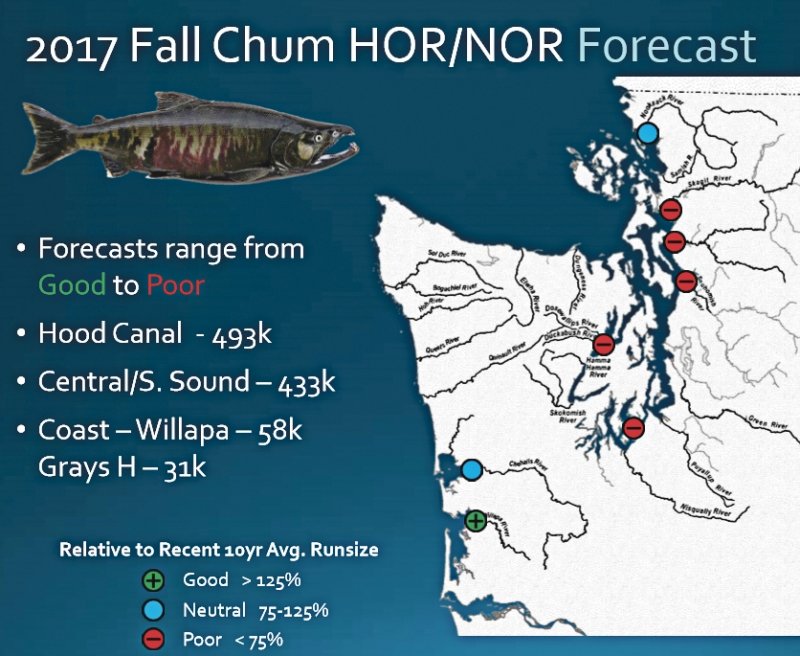

2017 projected returns for a specific salmon species in Puget Sound. Courtesy Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife

2017 projected returns for a specific salmon species in Puget Sound. Courtesy Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife

Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part series on salmon and the Key Peninsula. Read Part 2 here.

The survival of salmon is threatened. For more than a thousand years, salmon have been a life-sustaining centerpiece of Native culture. The miracle of their annual migration is a reminder that rivers and watersheds, estuaries and oceans are healthy. From orcas and bears catching live fish to eagles and stoneflies feeding on carcasses, more than 130 different species depend on salmon for survival.

Pacific salmon fuel a $3 billion annual industry, according to the Wild Salmon Center. They support tens of thousands of jobs and local economies and communities around the Pacific Rim. A report from the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) from 2012 stated that commercial and recreational fishing in Washington fisheries directly and indirectly supported an estimated 16,374 jobs and $540 million in personal income. Salmon accounted for a significant proportion of those numbers.

Randall Babich, who lives in Longbranch and has fished in Alaska and Puget Sound, has seen the decline firsthand. “Over my 48years of fishing, there have been tremendous changes from degradation of habitat to global warming and changes in the food chain,” he said. “The salmon have really been impacted.”

For nearly 1,500 years, the balance between harvest by indigenous people who depended on salmon and the natural ebb and flow of salmon populations were sustainable. But the arrival of pioneers in the mid-1800s led to new fishing techniques and the emergence of a market-driven economy, causing a decline in salmon populations. In addition to the effects of overfishing, habitat was degraded by logging, mining and irrigation. By the 1930s, large-scale dam projects posed additional barriers for migrating fish. According to the WDFW, the first salmon in the Pacific Northwest, the Snake River sockeye, was declared endangered in 1991. By the early 2000s, salmon were listed as threatened or endangered in nearly three-quarters of Washington State. These include the Puget Sound Chinook and steelhead and the Hood Canal summer chum.

The federal Endangered Species Act and Washington state law require development of recovery plans for diminishing salmon populations. Margen Carlson, director of Puget Sound Policy for WDFW, called this the “four Hs” of salmon recovery: habitat, hatcheries, hydropower systems and harvest.

In 2002, seven salmon recovery regional organizations made up of local, state and federal agencies, tribes and citizens were created to develop recovery plans and coordinate implementation. The largest is the Puget Sound Regional Organization and it, in turn, is divided into 19 Water Resource Inventory Areas (WRIAs). The Key Peninsula is part of the West Sound Watershed, which encompasses approximately 250,000 acres and includes the islands of Anderson, Fox, McNeil, Bainbridge, Ketron, Herron, Blake and Raft; the cities of Gig Harbor, Port Orchard, Bremerton, Poulsbo; and parts of Kitsap, Pierce and Mason counties.

Each WRIA works to establish recovery plans appropriate to its region, covering all or some of the first three “Hs.”

There are seven indigenous salmon species in the Pacific Northwest: pink, Chinook, coho, chum and sockeye salmon, and steelhead and cutthroat trout. All follow a life cycle of birth in a stream, migration to a large body of water to mature and then migration back to the stream of their birth to spawn and die.

Steelhead spend several years maturing in rivers before migrating briefly to saltwater. Cutthroat mature in saltwater but tend not to travel far from the streams of their birth. The other five species hatch in rivers or streams, guarded briefly by their mothers, who die within a few days or a month of laying the eggs. Fry hatch weeks to months later and depend on the bodies of dead salmon (or insects that also depend on those bodies) for nutrition.

While chum fry almost immediately head for estuaries to grow, the others spend three to 18 months in fresh water before migrating to estuaries and then the ocean. Chinook return to spawn two to six years later, chum and coho in three to five, and pinks have a strict two-year cycle from hatching to spawning. Sockeye mature in lakes and may remain there or migrate to the ocean before returning to spawn. Pink or humpback salmon is the most common. It is also the smallest and leanest Pacific salmon. Its flesh is described as soft and bland and is most commonly used for canned salmon. Chum is the second most common and is leaner than sockeye with firm, pale flesh. It is not farmed and is caught in Puget Sound in the fall and sold fresh. Coho is fished in the coastal waters of Alaska. It is less fatty than sockeye, with flavorful, medium-red flesh. Sockeye is second to the Chinook in fat content and has dark red flesh. It is caught in the Northern Pacific, sold fresh and also canned. Chinook (also known as king) is caught in North Pacific. It is the largest, fattiest salmon variety and may be deep red or white. It is sold fresh, frozen and smoked. [/box]

UNDERWRITTEN BY THE FUND FOR NONPROFIT NEWS (NEWSMATCH) AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, THE ANGEL GUILD, ADVERTISERS, DONORS AND PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT INDEPENDENT, NONPROFIT LOCAL NEWS